Could Google Be “Selling Personal Information” Under the CCPA?

A look at the principles underpinning a major class-action lawsuit against Google

Could Google Be “Selling Personal Information” Under the CCPA?

Google is being taken to court by California residents in an ambitious class-action lawsuit.

The plaintiffs claim, among other things, that Google is selling people’s personal data via the real-time bidding (RTB) process, without offering an opt-out. The case alleges that this violates the California Consumer Privacy Act.

The docket is 620 pages long, and—well—I’m not getting paid to write this particular article, so I confess that I haven’t read the whole thing in detail. It’s a complicated case drawing on several different areas of law.

So, rather than getting into this specific lawsuit, what I’d like to do is concentrate on one key question: Could Google be “selling” personal information, in violation of the CCPA, via the real-time bidding (RTB) process?

What’s RTB?

For a great explanation of RTB, let’s turn to cybersecurity supergenius Dr. Lukas Olejnik, who offered me this explanation for an article I wrote last year:

“RTB involves three parties: the website, the RTB auction operator and the bidders. When the user is browsing a site (or launching a mobile app, for instance) that subscribes to RTB ads, the operator of the RTB system learns about this visit. They then launch an auction, sending information concerning the user to the bidders”

The “bidders” in this scenario are bidding on the chance to present an ad to the user.

Is this really “selling” personal information?

Under the CCPA, I believe this could qualify as “selling” personal information. Here’s why:

The CCPA has a broad definition of “personal information,” which includes “internet or other electronic network activity information” and “inferences drawn” from such data “to create a profile” about a person’s preference.

A “sale” is any disclosure of personal information “for monetary or other valuable consideration.”

What’s “valuable consideration”?

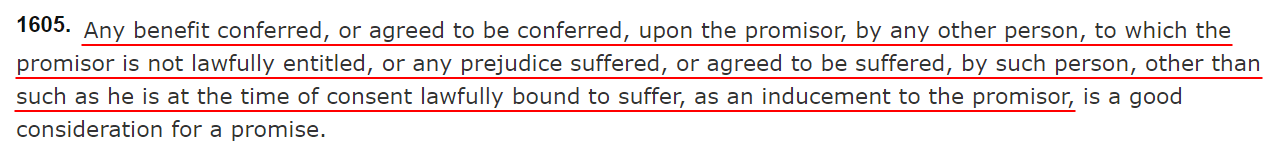

Here’s how California law defines “valuable consideration”, at Cal. Civ. Code § 1605:

This definition is very broad. Bidders don’t have to give Google money. Google just has to benefit from the RTB process to potentially bring the activity under the definition of “sale.”

Is it illegal to sell personal information under the CCPA?

No, but you must offer consumers an opt-out and respect their choice to opt out.

Hasn’t Google protected itself against CCPA claims?

Yes—or so it hopes.

When the CCPA took effect, Google created a new “restricted data processing” policy “to help advertisers, publishers and partners manage their compliance” with the CCPA.

What’s a restricted data processing policy?

Google’s policy is an attempt to bring itself under the CCPA’s “service provider” exemption. When you transfer personal information to a service provider, the transfer won’t qualify as a “sale” even if you benefit from it.

Likewise, Google stops using the information in such a way as to constitute a “sale", by instead sharing the information for “business purposes” as a “service provider”.

So Google just has to call itself a “service provider” and everything’s fine?

No. A “service provider” under the CCPA must fulfill certain characteristics—most importantly, it must operate under the instructions of its client business (in this case, “advertisers, publishers and partners”) via a written agreement.

Think of a “service provider” as being like a “data processor” under the GDPR. There are many differences between these two entities, but essentially, the business (the “data controller”, in GDPR terms) is in charge.

A service provider agreement must require the service provider to:

Only process the personal information it receives from a business for specific business purposes.

Not use, disclose, or retain the personal information for any purpose outside of the contract, unless otherwise permitted by the CCPA.

So what “business purposes” does Google use personal information for under the “restricted data processing” policy?

If a publisher has “restricted data processing” turned on for California consumers, Google only uses the data for conversion tracking and campaign measurement. These are valid business purposes under the CCPA.

So… case closed?

Not quite. It appears that it is the publisher’s responsibility to enable “restricted data processing.” Presumably, there are publishers who have not done so.

If there are indeed publishers who continue to send California consumers’ personal information to Google, without offering an opt-out, and Google continues to “sell” this personal information via the RTB process, this may constitute a “sale”.

Aren’t publishers liable for this?

Arguably, yes, but Google might also be liable.

If Google is “collecting” California consumers’ personal information, which can including “receiving” it, and “selling” it downstream, it doesn’t necessarily matter where it obtained the information from. Google would have to make those consumers aware of their “right to opt out” before selling their personal information.

So is Google going to have to pay up?

Again, I’m not going to get into the specifics of this particular lawsuit, but in general, there’s a huge issue with bringing this claim under the CCPA.

The CCPA’s “private right of action” only applies in the event of a data breach. And not just any data breach—a really specific type of data breach.

First, the data that has been breached must be “private information”, which consists of a person’s first name or initial and last name, PLUS another piece of data from a list of specific elements (SSN, etc). At least some of this data also has to be unencrypted.

Second, the data breach has involve all four of these interlinked elements:

Unauthorized access, AND

Exfiltration, theft, or disclosure, AS A RESULT OF

Failure to implement and maintain reasonable security procedures and practices to protect the personal information, THAT ARE

Appropriate to the nature of the information

This just doesn’t seem relevant to RTB at all. That’s not to say there has been no CCPA violation—but it might need to be enforced by the California Attorney General, rather than private litigants.

Just to reiterate: This is not a judgment about this specific case and I am not alleging that Google violates the CCPA.

Enjoy this post? There’s plenty more where that came from. I send a newsletter out once a week.